INTERFACE

Vast chain of Being! Which from God began,

Natures ethereal, human, angel, man,

Beast, bird, fish, insect, what no eye can see,

No glass can reach; from infinite to thee,

From thee to Nothing!

Alexander Pope (1688–1744), An Essay on Man (Fr. Epistle I)

In the age of Enlightenment, man and animal were envisaged as the middle links in a natural hierarchy. And centuries later, little seems to have changed. We see ourselves as closely connected with animals, and it is this human-animal relational aesthetic that is foregrounded in ‘Interface.’

The practice of visually representing animals in art may be seen as a dynamic interaction between ‘us’ and ‘them’. The forms may be interpreted as allegorical, symbolic, reverential, moralistic or simply pleasurable. Representation goes beyond the purely physical to involve metaphorical meanings. The artists inviting negotiation beyond an anthropocentric viewing through ‘Interface’ are A.V. Ilango, Biswajit Balasubramanian, Birendra Pani, B.O. Shailesh, C. Douglas, Harsha Biswajit, K. Muralidharan,

P. Elanchezhiyan, S. Nandagopal, Santhosh Kotagiri, Shalini Biswajit, Shivarama Chary and Thejo Menon. Each artist explores the premise of the human-animal connection through varied paths, bringing together multiple takes on an indispensable relationship.

Deriving imagery from his immediate surroundings, A.V. Ilango selects the animal on the street to make a powerful statement. Using readily available objects such as metal clothes hangers, garbage bags and a bicycle seat he captures the condition of the cow on the road. Skinny, undernourished and bloated with waste, the animal bulges at the abdomen, which is symbolically shrouded by garbage bags. A clever rendition of contemporary neglect of a once-favoured animal, the work allegorically speaks of societal consumption and waste. Also using found objects to create an animal form, Shivarama Chary on the other hand deals with its spirited nature. Constructed of springs, bearings and engine parts, the animal seems on a roll, and yet remains firmly grounded. The upward tilt of the tail creates a frisky demeanour suggesting a wagging tail spiritedly beckoning the viewer to play. Machine-made parts constitute a living form mirroring the mechanisation of contemporary living.

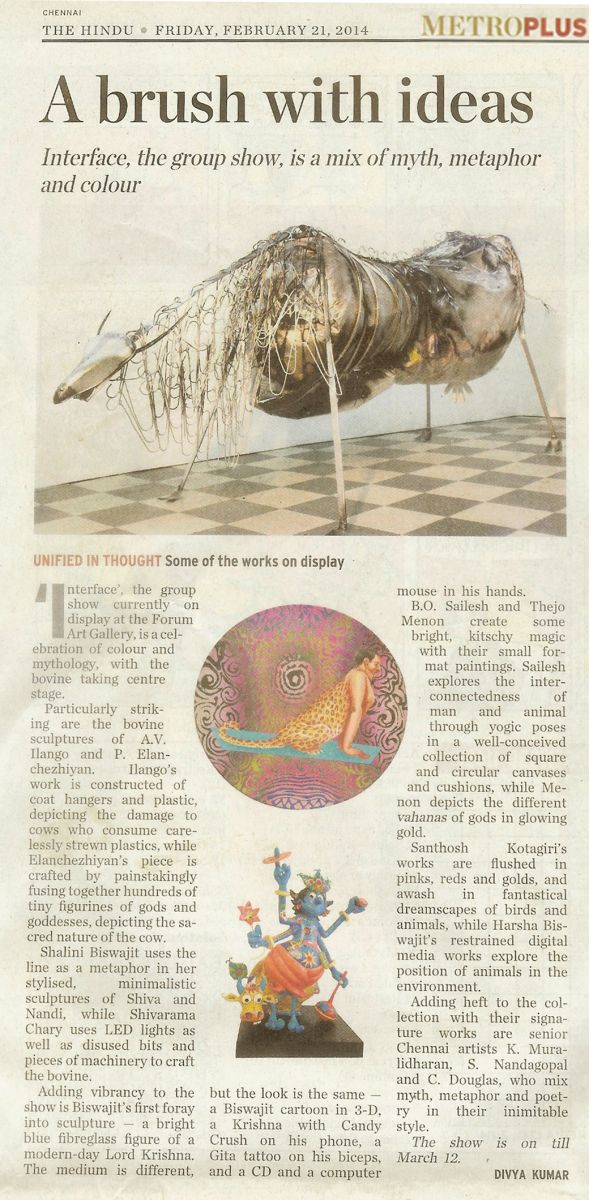

The distinction between human and animal is blurry in Harsha Biswajit’s graphic illustrations,which are paradoxically striking in their linearity. In his ‘The Animal is Absent’ series inspired by miniature painting and literature, man and animal inhabit a common space but are evidently binaries.His computer-generated imagery, sated with colours and patterns suggestive of machine-printed textiles,symbolically implies the impact of technology on society. In his exploration of duality and hybridity, animals are no longer of nature, but of technology, and the imprint of ‘machine-made’ is graphically defined.In contrast K. Muralidharan’s art draws energy from its inherent naivety through kitschy colour and fantasy. Although it looks primarily decorative, the artist’s concern with his discipline and the postmodern philosophies that guide it are evident. His search for a unique creative expression has taken him to the rich resources of childhood memories and imagination. The paintings are contemporised creations with roots in the traditional-mythological imagery of his childhood. His work embodies the influence of the surreal in the fusion of elements, man and animal. Another artist creating surreal dreamscapes is Santosh Kotagiri who harnesses the evocative translucency of egg tempera on rice paper sealed with an acrylic wash. Tantalisingly pensive in the choice of imagery and yet resplendent in the apposition of warm and cool tones, the paintings insinuate a subliminal union with nature. The soft dreamy forms glow with white lines that are shrouded in the darkness of dawn and dusk. Hints of gold and silver foil add to the otherworldly quality of the representation.

Better known for his metaphysical-themed paintings, C. Douglas offers a small bronze sculpture in the form of an elephant on its back supporting a baby on a boat. Given the unusual grouping, interpretations are many and varied the Buddha’s birth which followed Queen Maya’s dream of a white elephant representing the bodhisattva who is born Siddartha, and boat symbolising water, here amniotic fluid; the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke citing children, animals and death as the other side of life; and French poetry quoting elephants remembering past births. Douglas makes one rethink the associations that may be made, the interfaces that need to be crossed in juxtaposing three such incongruous elements.

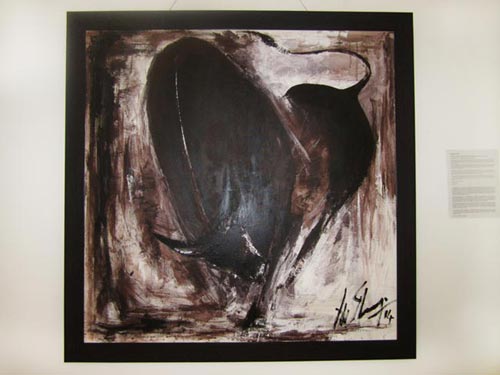

Animals are frequently seen within a religious construct where they are sited in symbolic or reverential positions, often as vahanaor vehicle to the deity. Shalini Biswajit looks to Nandi the bull, as a vahana of Shiva, seen as an intermediary into whose ears the believer may whisper a prayer. The animal holds the authoritative position of intercession between human and deity. Abstracted in form, the figure emblematically suggests the intangible presence of the divine and the power of prayer. In the openness of the sculpture and the coldness of brushed steel is envisioned the simplicity of the role of mediator and austerity in prayer. The bull is also the leitmotif of P. Elanchezhiyan’s works, whose small-format bronzes comprise exceedingly tactile bovine figurations. The artist delves deeper into the structure of the animal, creating the bull from the ideas that are embedded within it at a religio-cultural level. The bull is no longer just an animal; it is now the sum of spiritual and traditional beliefs that can be read beyond mere existentialism. It has become the aggregate of individual viewpoints rooted in Hindu iconography.

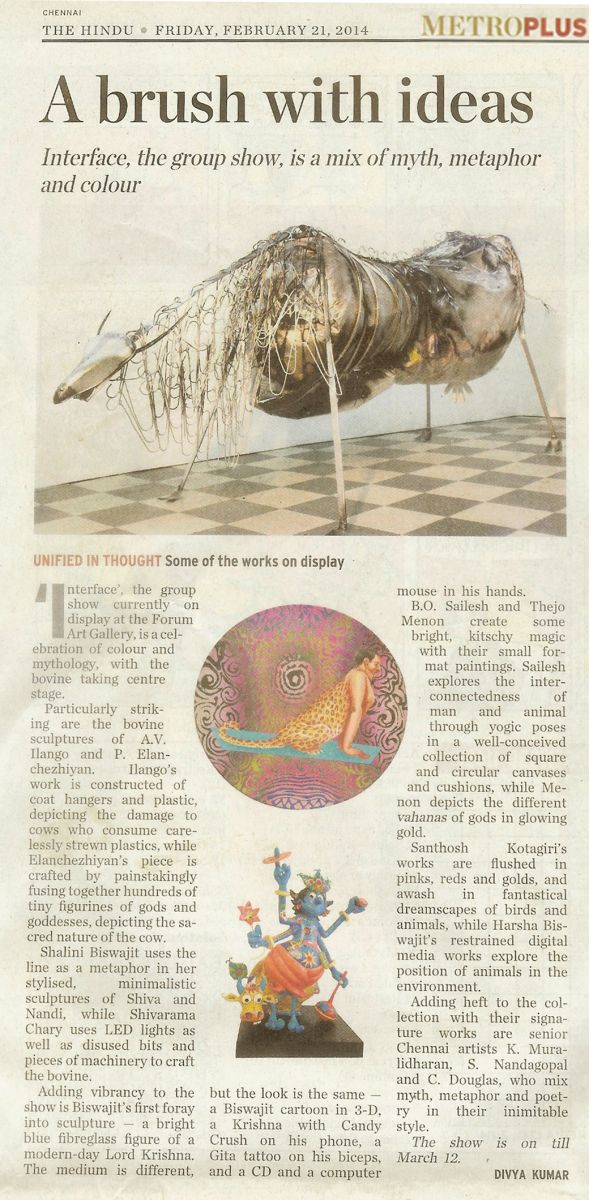

Further employing the human-animal consonance in sculpture is S. Nandagopal whose works are often inspired by Hindu mythology. Nandagopal works in his signature technique contemporising tradition to reexamine icons from antiquity. Rising metal shapes flecked with smaller copper-bronze fragments and touches of enameled colour play with the continuing theme of animal as divine. Rooted in the mythological past,his representations draw from the tradition of metal icons of worship, but are phrased in a modern-day idiom. In a similar vein, yet in a more facetious manner Biswajit Balasubramanian transforms his illustrations into the quasi three-dimensional format. Krishna and the cow are cast in fibreglass and painted with tongue-in-cheek allusions to popular culture. Their bodies are covered in painted symbols from past decades, with Krishna sporting tattoos that read ‘Krishna’ and ‘Gita’ and his cow featuring Zeenat Aman and Marilyn Monroe as gopikas. Multi-armed, Krishna’s iconography quirkily includes a compact disc and a computer mouse. Melding both materials and techniques with a good dose of wit, Biswajit bestrides illustration and sculpture in his caricatured construal of mythology.

In a linear style reminiscent of patapainting Birendra Pani encapsulates Chhau, a classical dance of Odisha in his ‘Handmade Memory’ series. His renditions attempt to focus upon niche identity, cultural tradition and history, connoting postmodern means to retaining nostalgic pasts. The virility of the Chhau dance with its martial origins is referenced through the enormous forms that fill the potent red picture planes. The animal masks marry the human face removing the interfaces that separate man from animal, suggesting power and dominance.From representations of purusha-prakriti, Thejo Menon refocused on the embodiment of woman and power. In her paintings she falls back on the symbolism and significance of icons. Incorporating auspiciousness through the presence of an actual object such as the engraved copperplateyantra from traditional Hindu ritualistic living, Thejo draws parallels with the elephant as representative of Lakshmi and the trident as symbolic of Shakti.

The power of the mind is the theme in B.O. Shailesh’s paintings, where the human body in yogic stances forms the pictorial trope gesturing towards the pliability of the human mind. According to him, only humans practice yoga, which in its imitation of animal and bird poses attempts to garner the power of nature through contortion. Working on canvases and cushions, the recurrent presence of the rounded form, be it in the fragmented egg from which the body emerges or the circus arena-like setting, further extends the idea of fluid resilience. Man is seen playing a role as suggested by the performance-setting, replete with curtains; the yoga position mimics the animal, which itself stands in an unnatural fashion with all four feet crammed into the smallest area as dictated by circus training. The human braves ordeals such as the elephant balancing on his back with yogic calm.

The elephant holds reverence through religion, and is also acknowledged for its intelligence and prowess. But these are not the only depictions encountered in visual art. The metaphorical use of the animal as encumbrance, memory, mythical, iconic and allegorical in the works of Shailesh, Muralidharan, Douglas, Thejo and Birendra respectively ascertains the various ways in which the human-animal rapport is perceived. The same animal assumes different meanings in each of these representations. Biswajit, Elanchezhiyan, Ilango and Shalini in their individual renditions of the bovine form address it variously as deity and as debris. It is this dichotomy of meaning that forms the premise of the interface between human and animal. We are similar, yet different. There are lines and boundaries separating the two, and yet these lines are often blurred, masked even. John Berger in his ‘Why Look at Animals?’ states, “The first subject matter for painting was animal. Probably the first paint was animal blood. Prior to that, it is not unreasonable to suppose that the first metaphor was animal.” Animals and humans share the earth, and they have been firmly embedded in our lives. It is indeed fitting that ‘Interface’ addresses the fine lines between human-animal relationships.

Swapna Sathish PhD

Following a research degree in art history from Milton Keynes (UK), Swapna received her doctorate from University of Madras. She is faculty in the Department of Fine Arts, Stella Maris College, Chennai. A freelance art critic, she has authored catalogues, reviews and contributed chapters to books.She has been awarded a post-doctoral grant from Charles Wallace India Trust for research in colonial art in the UK.

Artist Statement

Harsha Biswajit

The Animal Is Absent’ is a body of work that explores the nature of ‘animals’ and its place in the environment. In a broad sense, it can be thought of questioning the long-standing dichotomy between humans and nature. Today this idea of ‘nature’ as the background for humanity has dissolved, bringing everything into the foreground. Isn’t it ironical that in the age of the ‘anthropocene’ the ‘human’ has somehow been de-centered? Therefore the animal poses, as a mirror to society, perhaps reflecting that which is absent in our gaze. By de-centering the human, I try to blur the distinction between foreground and background thereby exploring themes of duality and hybrids. I also make use of computer programming that adds a dimension of chance to the aesthetic nature of the art object. Traditional Indian miniature paintings as well as more recent literary works such as Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’, Nietzsche’s ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’, the writings of Timothy Morton, and Derrida’s ‘The animal therefore I am’, amongst others have recently influenced my work.

This series of works represents an extension of the my work for the last two years that has revolved around deconstructing the environment, thereby questioning the nature of different actors within (humans, nature, technology, etc), and the relationships between them. My ecological curiosity was first sparked when writing my thesis on ‘climate change’ as a student pursuing a MA in International Political Economy. The obvious lack of ‘political will’ to confront the issue suggests there is a deeper ideological problem of perception towards the environment that science, despite its numerous findings, isn’t able to confront. As an artist today, my practice goes beyond facts and extends deeper than moral propaganda. It lies in utilizing this parallel platform to provoke and engage the viewer by exploring and representing a world behind such choices.

A.V.Ilango

The following news in DC, Chennai is the basis for this Installation.

Mountains of garbage line along the road side, spewing degradable and non-degradable waste. Emaciated cows and calves, desperate for food, tug at the plastic bags. One sip of liquid from the hellish Hades and the cows are sick for life with diarrhea and dysentery. This is only one of several thousands of illegal dairies in the country producing toxic and unhygienic milk.

The open garbage bin, rotting and putrid, is the second step in India’s abysmal waste disposal chain, the first being the lack of segregation in the household and usage of plastic bags for waste disposal. Abundance of plastic bags from every conceivable source is a boon for the householder, who stuffs all the garbage into them. The smell of food draws the hungry cows to the plastic bags.

But to get at the food, they must first undo the knot that ties the plastic bag. But as herbivores with no canine teeth, they cannot rip open the bag. So they eat the thin plastic bags, garbage and all. Over time, the rumen fills up with plastic bags, becoming a concrete block, leaving little space for food to reach the stomach. The bags take a toll on her digestion and, gradually, she starves even as the toxins leach into her bloodstream.

Lead, cadmium, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and hundreds of other chemicals proceed to slowly kill her. Then gnawing pain sets in and gnashing of teeth begins. She lies down preparing to die. The butcher is waiting and is soon at her side as she struggles to breathe. In a trice, our cow, having served humankind with her milk all her waking life, becomes meat and leather.

These are India’s plastic cows

Rukmini Shekar, Deccan Chronicle, South India.

Biswajit Balasubramanian

As a cartoonist, transitioning from a flat surface to a three dimensional one has been an exciting foray that brings to life my world of characters. The various attributes of Krishna have always been a source of inspiration for me and I have over the years ‘painted’ him as a humour based avatar that is all encompassing. He never ceases to amuse me and the sculpture in fibre glass has all the trappings of today that make him free spirited and as ‘current’ as ever.

P. Elanchezhiyan

Man and the bovine have coexisted since time memorial. Born in a village in South India, I have grown up with these bovine animals, observing them close and learning from them, and being inspired by their majesty, grandeur and grace. The bull is an object of reverence and I have superimposed the various figurines of gods and goddesses on the anatomy of the bull to reinforce the divinity.

K.Muralidharan

Indian mythology is a constant source of inspiration for my creativity where animals and birds play a key role in the unfolding of stories and events. They exist in my fantasy world and I use the imagery in my work to connect with the characters, or at times to convey a message or as mute spectators in the drama of my canvas.

S.Nandagopal

In my sculptures I have attempted to integrate the figure with the abstract. Coloured enamel also adds to the visual effect.

The four decades of his practice as a sculptor have generated in Nandagopal a concentrated sensibility of the Indian idiom narrating and unraveling it simultaneously. His ability to integrate linearity and flatness in his sculptures adds a painterly dimension to his work and imbues it with graphic quality. Each element be it man or animal have the potential energy to burst out of the composition giving the ‘heros’ a sense of heightened animation. The use of commonplace found objects lends a strangely imaginative contemporary idiom that is uniquely his own. Myths and legends add strength and magnificence to his forms but certainly their references are kept alive by a sense of respect and faith in his cultural heritage. His narrative sculptural work in copper and brass constitutes one of the most important collections in contemporary Indian sculpture.

Santhosh Kotagiri

I believe in subconscious, dream state imagery as the real reflection of the self. It embodies a freefalling organic metamorphosis where all universal elements merge and fall apart. The imagery of man, animal, plant in a symbolic, surreal state forms the major basis of my work. I use gold and silver leaf to create a mesmeric quality that reveals yet hides and aptly questions my concept of –what is real? . And what is imaginary? A cat, a dog, a fantasy, a bird, a talking tree and whispering branches play their roles against solemn men and women sharing a common surreal landscape.Here the human experience is magnified symbolically and allegorically. Man’s personal, cultural, social and political musings take a backstage and are fed into the irrational structure of my subconscious, expressing a sense of liberation and freedom.

Shivarama Chary Y

Owning a pet is an expensive proposition that requires time and resources. Hence I ‘created’ one from waste using found objects that will be ‘maintenance free’ sans the frills and fancies. It appeals to my imagination and disposition.

C. Douglas

The child and the upside down elephant in a boat - child and animal at

''The Other side '' in Rilke’s concept .water, boat in Foucault’s concept

''The voyage at once a rigorous division and an absolute Passage.

In one sense, it simply develops, across a half real, half imaginary,...

the river with its thousand arms, the sea with its thousand roads,

to that uncertainty external to every thing''.

Shalini Biswajit

I find the process of painting or sculpting an engaging exercise or a sadhana where my object of meditation takes shape on the surface. The emerging deity in this body of work is Shiva. He is dramatized as a metaphor or symbol and is accompanied by the Nandi the bull, the Vahana or vehicle that he rides on. According to Hindu iconography, the Vahana complements the energy of the deity. Loved, nurtured and worshipped, Nandi represents strength and virility that is reflected in both the served and the one that serves. The reciprocal relationship allows the magnetic flow of divinity to pass through back and forth. A devotee whispers a prayer into Nandi’s ears believing it will be directly conveyed to the lord. The Mediator thereby holds the key that unlocks the grace of the lord.

Birendra Pani

My present series of works are related to the contemporary material culture and human life and the negligence of the local place, culture, history, memory and identity in present time. The consumerist attitude has penetrated deep into the human psyche. Human beings are consumed by the commodity rather than they consuming it. In my works, I explore the struggles, contradictions, dichotomies and critical reflection of the embodied self with change in value, knowledge and culture in our present society and life. I have extensively used body parts like brain, heart and other organs, and everyday objects like capsule, syringe, blade etc to create a new visual language. Deriving from life experience, my idea is to create a new vision by the juxtaposition of the above experience with the rich legacy of diverse visual culture and sensibility with vast tradition of Odishan miniature and Pata painting, stone carving, monumental feeling of temples and dance forms like Gotipua dance and Chhau-dance in Odisha. The attempt is to create a new phenomenology and reinvention of ‘self’ in a globalized and yet localized world.

Thejomaye Menon

Animals and birds play a vital role in our scriptures. Every deity is accompanied by a bird as a vehicle or in the back ground quietly signifying strength and valour befitting the God or Goddess.On the flip side there is so much apathy and disregard in our real world. I have brought out these images as a reflection of my understanding of their importance given in Hindu iconography and the parallel qualities of that particular deity.

B.O. Shailesh

My work of art is the reflection of a mind through form and colours and tries to achieve new dimensions to painting on a par with my mental attitude. Yoga is kind of typical exercise which has beneficial effects for body, mind and spirit.

Yoga is one of the powerful movement of the body which keep this element fit, thus this has been fascinating me to work in this yogic forms and thus paintings are very personal which represent human body the beautiful element in this earth.

In this particular painting series yogic form gives aerobic movements which are influenced by animal’s ego. To show the flexibility, self curing capacity and to get rid of negative thoughts the animal figures emerges.

Animals observed in nature and noted for their particular abilities and accomplishments. Many postures require you to be an animal pose, in the hopes that we can emulate their skills and power. Yoga poses also come from other things in nature.