M. Senathipathi is an artist who works with the conviction that he is answering his life’s calling. He is a veteran on the Chennai art scene, having learned his profession in what was the premier art institution in south India, the Government College of Arts and Crafts, Madras, and mentored by stalwarts such as K.C.S. Paniker and A.P. Santhanaraj.

Born in 1939 into a land-owning family, Senathipathi spent his growing years in a small village near Maduranthagam in Chengalpet district, Tamil Nadu. Three-quarters of a century ago, the village was a pristine world unto itself, partially secluded with little access to roads, and therefore lacking motor transport. Only bullock carts plied between the neighbouring villages, thus enforcing a slow pace of daily living. Senathipathi’s father administered the agrarian practice of the lands and hoped that one day his sons would follow suit.

A Stimulating Childhood

Growing up in idyllic surroundings, Senathipathi remembers the colourful gaiety of temple festivals and religious rituals that made a lasting impression. His earliest reminiscences of an education are of the thinnae pallikoodam, an informal setting at the front of his home where a local elder would share his knowledge with the young children of the village in the oral tradition. Here he was introduced to Tamil literary classics such as Thiruvasagam, Thirukkural, and Manimekalai. Experiencing the epics in the oral tradition without references too written texts permitted flexibility in imagination and interpretation. It was at this time that he also witnessed religious murals being painted onto the walls of his home, and in sheer fascination set about replicating them on any surface he could. This act set free his love for drawing, allowing him to populate the walls of his home with figures and compositions. In hindsight, it was these three sensory occurrences – his experiential awareness of rituals and festivals, his auditory experience of the epics, and visual involvement with the murals – that set Senathipathi on a path of creative expression.

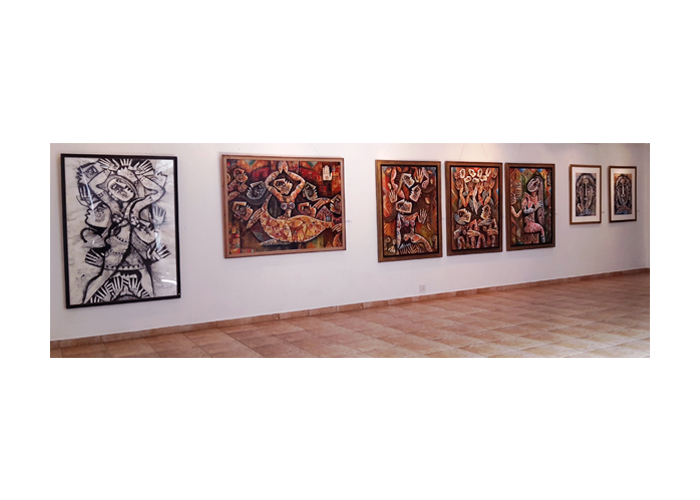

In school he won prizes in all the art competitions and it was foreseeable that his drawing master who nurtured his talent, encouraged him to pursue higher studies at the Government College of Arts and Crafts at Madras. Senathipathi enrolled for the painting diploma and completed the mandated years of study in April 1965. At his first group exhibition following his graduation, he received the impetus to work hard as an artist when a gallerist bought seven of his works. Committed motivation and diligence have stayed with him ever since pushing him to also work with taxing materials and techniques such as metal reliefs in silver-plated copper.

He recalls, however, that his life as an artist was not easy, for it was particularly unpredictable and hinged on the whims of a diminutive art market. Within the first year, his family encouraged him to accede to a routine job to pay the bills, while practising art in his free time. He worked as an art teacher, and it was at this point in time that he met with his former teacher Paniker, then Principal of the School of Art. This meeting was to alter the direction that Senathipathi’s career would take.

Paniker’s Concept of a Commune

A visionary with a mission to further the cause of art and artists, Paniker was of the opinion that creativity would be compromised when artists, who found it challenging to sustain themselves with income from art alone, took employment in the outside world. To counter this, he envisioned a community of artists who practiced art as a profession, aided by additional revenue from creative crafts such as batik and terracotta. In the 1960s and ‘70s, tourists to the city of Madras, mainly Americans, bought these crafts as souvenirs, providing extra income for the artists, which went towards sustenance and art materials.

When Senathipathi met Paniker in 1966, he was introduced to the concept of the artists’ collective and encouraged to join the mixed group of senior artists and fresh graduates in the new venture. As such, the Cholamandal artists’ village started on the outskirts of the city of Madras with thirty artist members. Today, almost half a century on, half of the pioneering group have passed on, and a few have moved away to other cities or countries. A new generation of artists have taken their place and the community continues to thrive. Senathipathi, a young founder member of the group owes much to Paniker’s vision and has lived his entire career within the sanctuary of Cholamandal.

The artists’ commune was not initially utopia, but rather, the initial years there were fraught with challenges. However, he was grateful for being able to work in an inspired environment on his own terms, and to develop his individual style. He is mindful of the fact that because of the concept of the artists’ collective, where steadfast engagement with craft augmented the artist’s arbitrary income, he was able to commit himself more to art and work harder with the creative aesthetic. An active member of the artists’ village, Senathipathi has been President of the Cholamandal artists’ association for nearly thirty years, helping to maintain the commune and keep it alive.

Contemporising the Epics

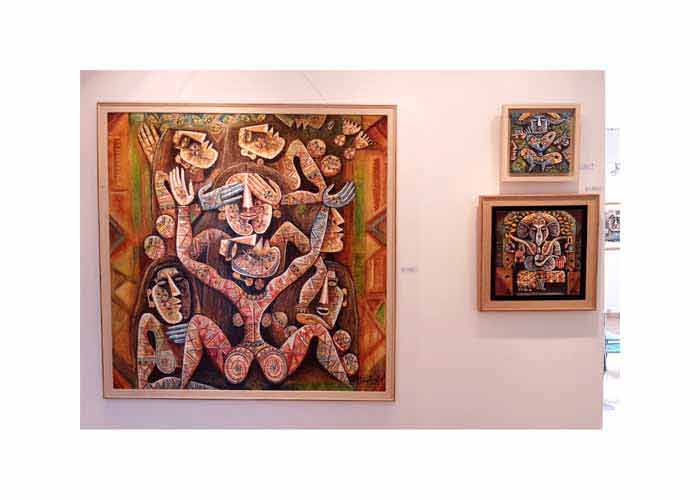

Senathipathi has relied on his past experiences to people his works. While his forms have always centred on the gods and goddesses of Hindu mythology, his themes veer away from the religious core and are in fact contemporary societal interpretations of these narratives.

His approach to the mythological subjects that he chooses to render are not solely based on the narrative, but are premised upon the societal implications they portend. This is evident when he states, “by recalling the stories I heard during my childhood days, I picture the event and present it in my paintings, in my own way. This helps me retain my originality.” He has consciously chosen not to go back to the primary textual sources, choosing instead to rely on aural recollection. His motifs are sourced at a subconscious level from his childhood’s vast visual repertoire. The embodiments of a million narratives extolling the virtues and vices as articulated in Hindu mythology, addressed through oral storytelling culture, and their visual support from the paintings and ancient sculptures in the temples along with casual encounters with folk and tribal elements in every day life. This cultural capital forms his cornucopia, and it is into this that he delves time and time again.

The stories serve no higher meaning and allegorical narratives become unimportant. Instead these stories become vehicles through which his concerns for society are made manifest. An anxiety for the future is implied in his paintings bearing titles such as ‘Insecurity’, ‘Chaos’ and ‘Hide and Seek.’ Another painting, titled ‘Draupadi,’ may refer to the wronged woman in the Mahabharata but in his canvas she epitomises the insecurity in human interaction. His protagonist rises above the story-telling aspect to symbolise the emotional significance. Draupadi can be read as an icon of vulnerability, a target of sexual violence. A subject he has engaged with through the years, Draupadi is visualised as a central figure in the composition with arms and head raised heavenward in imploration, while being stripped of her modesty by lecherous males. The presence of numerous hands in the composition adds to the disconcerting lewdness.

Other subjects that have been represented often in his repertoire are ‘Krishna and the Gopis,’ and ‘Ganesha.’ He says that they are not meant to be viewed as gods, or read as icons for worship. Instead, they are to be seen merely as ubiquitous images that are interesting in form and hence, worthy of replication and representation. According to him, the “form achieved through the process of drawing is more important than the iconography itself. The stories themselves are not significant. The Mahabharata and Ramayana are interpreted as aspects of human behaviour.”

An Individual Style

Exploratory at the start of his career, the plethora of visual imagery that Senathipathi has carried forward from childhood has been interpreted in a unique manner. According to him, “Hinduism is a collective consciousness, and hence there is no need to see and visualise. I do not have to see and replicate images, because I know the stories, and what is projected is from within me. It is my version of what I see and interpret. Nothing is copied – it is mine, my individual, independent style. I take pride in the fact that my work is recognisable. I think that is very important for an artist.”

To Senathipathi, drawing is a significant activity, and by repeating the process through the years, over and over again, some features have become recurrent in his work, thus developing into a personal style, which has evolved very slowly. His work has been decorative, and veering towards abstraction, yet has never lost sight of the figurative. It exhibits propensity to two salient characteristics of the Madras Movement mainly in its nativist derivation and the linearity of representation.

His pen and ink works are painstakingly and systematically executed. A large sheet of paper is stretched flat and dampened with water. Working with pen and ink on moist paper creates contrasts of sharp lines and sfumatesque effects that tease and entice an alert eye. The disparity of styles employed, namely the stark precision of the line and the subtle haziness of the wash technique, exist side by side. The whole process is spontaneous, with a predetermined theme in mind, and forms are worked directly onto the paper without the aid of studies.

In his paintings, the forms are drawn onto the canvas and built up into a textured artwork. Once this layer is dry, colours are applied and final details are drawn in. Working on large-scale paintings allows the enormous forms to be populated with smaller versions of his characteristic forms. It is the drawing is most important, both before and after the addition of coloured pigment. The act of painting itself is indeed secondary. Inevitably his style is illustrative, rather than painterly. It stems from the fact that he considers drawing most significant. The flattening of the picture plane has been broken into smaller components and creates an impression of being decorative, pushing his figurative work to the other end of the spectrum from the naturalistic.

Senathipathi’s flattened forms decidedly shun three-dimensionality. There is no modelling through colour or form, and in its place instead is a celebration of the flatness of the picture plane. While his earlier works from the 1960s were figures that convincingly occupied space, there has been a clear shift towards two-dimensional flattened space where textural patterning takes precedence. His present-day forms are no longer earthy and squat, but are instead slim and lithe, almost paper-thin. The faces are prominent, with smaller bodies that seem to lack skeletal structure.

In the process of filling in the picture plane, the artist uses a dominant form and fillers, which often consist of sharp lines that intersect one another providing the element of harshness in otherwise mellow compositions. These intersecting lines with loose ends create a sense of the tactile and are aided by raised textures built into the picture surface. The larger form is usually figurative and comprises the premise, which is supported by motifs derived from other visual media such as metal relief sculpture. The usage of the motif as a repeat further creates a textural aspect to the work. The modest motif is layered into the composite.

The themes are of the Hindu pantheon, but the form is suggestive of the temple sculptural relief tradition. It is not surprising that besides drawing and painting Senathipathi has chosen to work on metal relief-sculptures. Frontality seems to be significantly prominent, and is reminiscent of the icons of worship that were a part of his childhood visual experience. The hands are almost always open-palmed, reiterating the posturing of the deity, especially in sculptural renditions. The frontal and the profile exists side by side, in a way suggestive of a dimpled chin and otherwise allusive to two faces in profile joined by pursed lips.

Postmodern Inclination

On closer observation, the faces in his canvases have the mixed perspective of the western Cubist idiom in their frontal depiction of the nose alongside the profile view of the lips. But in the working of intricacies the artist resorts to his nativist inclinations, drawing from the vast repertoire of motifs ingrained in his mind. The forms are resonant of the modernist paradigms within which he was schooled, but breathe the postmodernist rootedness to his cultural tradition. Senathipathi speaks of his love for Vincent van Gogh, Paul Klee and other modern masters, but revels in his borrowing from local visual motifs. The pervasive presence of Dravidian sculptural craftsmanship in temples and the linear tradition of south Indian mural painting are two sources that he has delved into. Both these sources assert two-dimensionality, where line creates form in the absence of modelling. Indeed Paniker had stressed on the need for a nativist stance to fuel creativity, as opposed to directly borrowing from western modernism. This rootedness and truth of expression was seen as essential to creative originality. Indeed the multiplicity of imagery creating a densely-woven configuration speaks loudest of his nativist leanings in a postmodernist sense. After a good fifty years at his profession, Senathipathi, in his seventy-fifth year, is still enthusiastic at the prospect of artistic creation and is active at work on his canvases.

Following a research degree in art history from Milton Keynes (UK), Swapna received her doctorate from University of Madras. She is faculty in the Department of Fine Arts, Stella Maris College, Chennai. A freelance art critic, she has authored catalogues, reviews and contributed chapters to books. She has been awarded a post-doctoral grant from Charles Wallace India Trust for research in colonial art in the UK.